Pages from the past May 3, 2018 – Posted in: In The News – Tags: architecture, areca books, Books in Malay., Cultural Heritage, Ecology and Environment, history, Journeys, Nature, Social History, Visual Arts

DRIVING into Seberang Perai is almost like entering a different state altogether. The casuarina trees that pepper the coast of Penang as you head towards the iconic bridge fades into the silhouette of the hills that cradle the island. Warehouses, large but low concrete buildings, and blocks of shophouses greet you in Seberang Perai, the strip of land often referred to as “the mainland” by Penangites.

DRIVING into Seberang Perai is almost like entering a different state altogether. The casuarina trees that pepper the coast of Penang as you head towards the iconic bridge fades into the silhouette of the hills that cradle the island. Warehouses, large but low concrete buildings, and blocks of shophouses greet you in Seberang Perai, the strip of land often referred to as “the mainland” by Penangites.

It is a world apart from the giant trees that shade some of Penang’s historical streets, or George Town’s narrow lanes, opulent clan houses, century-old places of worship and grandiose colonial buildings which dot the island. In her latest book, Province Wellesley — A Pictorial History, historian, heritage activist and author Salma Khoo Nausution offers an insight into just how rich this lesser known part of Penang truly is.

Pages of the past

Pages of the past

“Much of Seberang Perai’s built heritage is neglected,” confides Salma, who has been painstakingly collecting material for the book over the years. “Yet there are isolated examples of heritage which is still intact,” she adds.

In 2015, Salma, who’s also the Penang Heritage Trust vice-president (PHT), started putting her research together. “We have a lot of images of George Town and Penang island but it’s not easy to find images of Seberang Perai,” she says, adding that an exhibition and a series of lectures about Seberang Perai’s rich past were presented in the lead-up to the book’s launch.

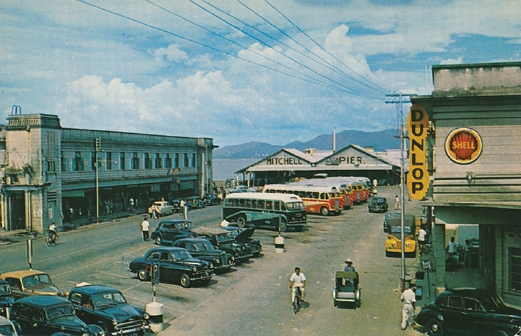

ProvinceWellesley — A Pictorial History is a collection of more than 200 photos of the early days of Province Wellesley — from ancient artefacts of the Siamese-Kedah Kingdom and the industrialisation of the mainland during colonial times to post-war Penang. It also highlights the different components which made Seberang Perai a thriving port in the 1800s, fertile land for agriculture, advancements in transportation systems, strategic locations of rivers and crossings as well as the strength of multi-cultural communities.

“As a Penangite, it’s so exciting to discover the history and heritage of the different communities in the book,” says Trevor Sibert, one of the speakers at PHT’s The Seberang Perai Story lecture. “It opens doors to learning more about the minorities who helped shaped Seberang Perai.”

Province of progress

Province of progress

Named after the first Marquess Wellesley, Governor of Madras, and the Governor General of Bengal Richard Wellesley, the strip of land belonged to the Kingdom of Kedah before the East India Company acquired the land in 1800. During the invasion of Siam in Kedah, many, especially the Malays, fled and found refuge in the vast lands of Province Wellesley where they began farming. By 1835, Province Wellesley’s population had boomed to 46,880, close to 7,000 more inhabitants than that of Penang island.

The mainland became a hub for agricultural resources — rice, tapioca, pepper, coffee, spices, coconut, with the most profitable being sugar. Pioneered by the Chinese and Europeans, the business brought in both heavy machinery and indentured Indian labour. “With increasing awareness of the importance of ecology and environment, we’re now seeing the value of industrial heritage and cultural landscapes,” Salma says, noting that prior to this, urban conservation revolved around monuments, historic districts and the people who inhabited those areas. “We need to understand the industrial and environmental history of Seberang Perai as the basis of identifying how we can conserve this sense of place through planning and sustainable development.”

Many perceive that restoring heritage is equivalent to stopping progress. However, as Salma points out, it isn’t about stopping development, but proper planning. “Early identification and safeguarding of our heritage coupled with good planning will bring development in such a way that the heritage places are centralised as local attractions, landmarks and landscapes that enhance the quality of the developing district.”

Using the past to progress

As Salma shares, the importance of heritage lies in how it provides a sense of place which evokes social memory, something she feels is important for people of all ages. “Young people should grow up with a sense of the richness of the past, whereas old people need to familiarise with places as they easily feel disoriented if they cannot recognise places which the feel they should know,” she explains, adding that Seberang Perai is changing at lighting pace, hence the urgency to identify historic landmarks and cultural landscapes are of utmost importance. “These landmarks anchor a sense of place,” Salma continues.

One of the youngest council members of the PHT, Sibert, 33, echoes her sentiments. “For us young people, it’s important to remember our roots, especially for the community in Seberang Perai. Not much is known and there isn’t much literature out there about this side of Penang. Hopefully this pictorial history will pique the interest of the younger generation to explore the heritage we have here,” he says, noting that almost 75 per cent of the audience for PHT’s The Seberang Perai Story lecture were above the age of 45.

“There are just so many stories — from generations of families who have been living in Seberang Perai that we haven’t heard of yet,” says Sibert, who, during the lecture series, presented a talk on the Eurasian community’s involvement with Province Wellesley’s crucial railway history.

For Salma, who was born and bred on Penang island, Seberang Perai has remained a place that continues to fascinate her. “I know that many people who grew up or live in Seberang Perai feel passionately about their heritage,” confides Salma, who remembers the ferry rides to Butterworth and sprawling emerald paddy in the North with great fondness.

But the future of Seberang Perai’s heritage, she says, lies in the hands of the people who call it home. “As the primary stakeholders, they need to find a collective voice to champion their heritage. People like me can share our experiences and insights but ultimately, the Seberang Perai people have to champion their own heritage.”

Somewhere beyond the industrial warehouses and concrete shop houses lurks a rich history — a landscape of peoples, places and culture that are testament to Seberang Perai’s glorious past. Now, it’s just a matter of unearthing it. — Kerry-Ann Augustin

This article first appeared in the New Straits Times on 11 September, 2016