Forest plants in watercolours: Malaysian artist documents Orang Asli knowledge and culinary practices January 12, 2022 – Posted in: In The News, Reviews

Vincent Tan

28 March 2021, CNA

KUALA LUMPUR: Seated at her home studio, Syarifah Nadhirah Syed Abdul Rahman carefully applied different shades of green watercolour for a daun semomok painting.

Harvested from the forests, the plant’s leaves are used by the local Orang Asli tribes to season food. When cooked, its insect-like smell disappears and is replaced by a pungent, appetising aroma.

“The communities I talked to also said that daun semomok only grows in certain parts of the forest where there is the right soil conditions and humidity, so they take it as an indicator whether the forest is also healthy or not,” she said.

Around her work area, more watercolour paintings and pen sketches of indigenous plant species were spread out to dry underneath the air-conditioner.

Syarifah Nadhirah, 27, launched “Recalling Forgotten Tastes” in November last year, an illustrated book featuring forest edibles and the traditional cuisines of Orang Asli communities in Selangor and Negeri Sembilan.

The book is the result of a year-long pursuit, in which she followed the indigenous people on their foraging trips in the forests, and learned about the different qualities and uses of each plant.

In addition to the watercolour illustrations, the book also contains excerpts of conversations with her Orang Asli guides, detailed explanations of how their meals are made and descriptions of her foraging trips.

Her aim in publishing the book was to preserve the Orang Asli communities’ knowledge about the forests before both forests and knowledge disappear.

Starting out

Syarifah Nadhirah, who runs a design studio by profession, attributed her fascination with different cuisines and their ingredients to her mother.

It was her mother’s interest in cooking that sparked her interest in culinary practices. The idea to focus on documenting the different herbs and plants used by Malaysia’s indigenous Orang Asli communities came about after a conversation with anthropologist Dr Rusaslina Idrus at Universiti Malaya.

“The idea for this book project started in 2019 after I was inspired by the conversation I had with her. She had been working with the Orang Asli communities for a really long time, so she introduced me to her contacts in Negeri Sembilan,” said Syarifah Nadhirah.

During her visit with Dr Rusaslina to one community’s Christmas celebrations, one of the local women brought them on a garden tour.

“Most of what she told us was never recorded, or just an unwritten oral history of the plants they use and their cuisine, so it just triggered me to start documenting all these stuff,” Syarifah Nadhirah explained.

In addition, she said, having friends studying botany and other ecology subjects definitely helped feed her thirst for knowledge.

Along the way, she made friends with members of different Orang Asli communities. The Temuan tribe in Selangor, for instance, brought her and her friends to visit the Kuala Langat forest reserve area, which is now in danger of being degazetted for development.

“They really changed my perspective on plants and the natural environment,” she explained.

Forests as source of food

“Indigenous food is quite different from what we know. What you’ll eat that day is determined by what plants you’ve foraged from the forest, and the season of the year.

“For example, during the dry season, some plants can’t be found and the community will farm a certain type of paddy or starchy roots for carbohydrates. If it’s the wet season, it’s harder to find animal protein because animals will not go near certain areas,” Syarifah Nadhirah recalled her foraging trips with the Orang Asli.

In a trip to Pahang, Syarifah Nadhirah was introduced to a type of bamboo dish, which contains not just the bamboo shoots but also the beetle grubs feasting on the shoots.

“It was something like the sago worms in East Malaysian cuisine, and they ate it raw or fried, because the grub was quite fat and juicy and non-toxic. I just watched the rest eat them,” she recalled.

Another edible she was introduced to was daun kulim from the kulim tree, which was mainly used as an accompaniment for fish dishes.

“It smelt a little like turmeric, but much stronger and aromatic,” she explained.

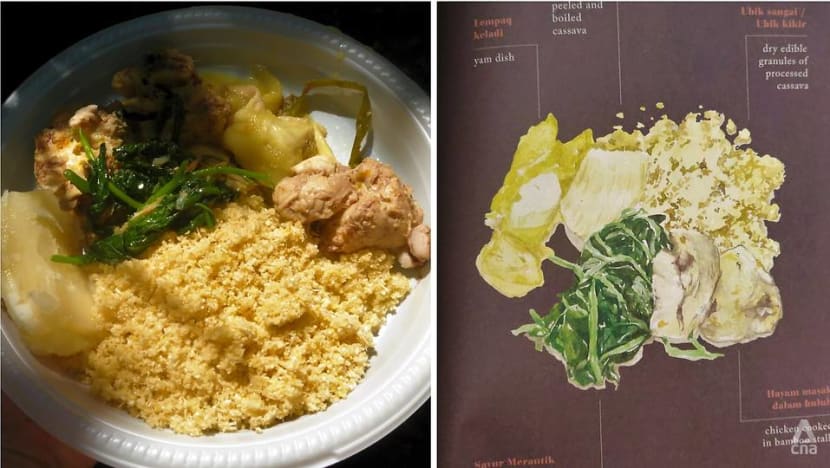

Then there was sayur meranti, which despite its name, is not derived from the meranti or Shorea tree.

“It’s something like spinach, but much more bitter, so what they do is to steep the leaves in water for a few days to leach the bitter flavour away, then dry-fry the leaves with some ikan bilis (anchovies) as a dish,” Syarifah Nadhirah said.

Disappearing forests and knowledge

Working on her book took longer than expected, due to Malaysia’s movement control order instituted in March last year to control the spread of COVID-19 and trips outside of Selangor were almost out of the question.

“When I go for foraging trips, of course my friends or the guide will point out different things that are there, not just the edibles. It’s become a nature education guide in fact,” Syarifah Nadhirah said.

Some of the plants have medical uses for the indigenous communities.

“Like this plant, it’s called setawar and it grows along rivers and soaks up a lot of moisture. My guide would point out that it has an ‘umbut’ – the young shoot.”

“The plant itself can’t be eaten, but you can squeeze out the moisture inside the shoot and it’s good for treating coughs and fever,” she said.

In the course of archiving the plants, Syarifah Nadhirah also learned about the communities’ struggle with disappearing forests.

“Like the Temuan community in Kuala Langat, their forest is being threatened and already diminishing at the edge. Certain plants like mengkuang (screwpine leaves) are disappearing, and it’s an important part of their weaving craft, which they now can’t practise as much as they used to,” she said.

She contrasted the Kuala Langat folk’s predicament with another Semai community in Pahang, which could still access traditional forests.

“Their (the Pahang tribe) cuisine is still pretty traditional, but for the Orang Asli communities closer to the city, either they eat like us, or their indigenous knowledge is slowly disappearing, because the forests are also disappearing,” she said.

Syarifah Nadhirah discovered that as she spoke to the indigenous people, they tend to recall more traditional knowledge and share with her.

“That (knowledge) is still embedded, just that they don’t have a chance to practise them,” she noted.

Having done about 50 illustrations of the indigenous plants, only 30-odd illustrations made it into her book.

“Some of it was difficult to identify, and others, my Orang Asli friends and guides asked me to exclude to prevent these plants from being poached and overexploited,” Syarifah Nadhirah said, recalling the insatiable demand for roots such as tongkat ali and kacip fatimah, both popularly used as reproductive tonic, or agarwood for aromatics.

Race against time and development

For Syarifah Nadhirah, the choice to depict these plants in watercolour came naturally to her because of her art and design work, and also because it felt more meaningful than just taking a photograph.

“It also harks back to the old-style naturalist and botanical illustrations,” she smiled.

Continuing the effort from “Recalling Forgotten Tastes”, Syarifah is also working on two other similar archival projects, one of them is to turn the research from the book into visual maps of edible plants.

The other is to eventually build an interactive site which provides visuals and sounds of the forests roamed by different Orang Asli communities throughout the peninsula.

Underpinning these efforts is the realisation that this is a race against time before the forests diminish as development progresses further inland, and the knowledge thereof disappears.

“We’re already really late, actually all of these plant illustrations are really just the tip of the iceberg. I’m sure if you talk to more communities, you’ll unearth even more plants that each local community uses,” Syarifah Nadhirah said.

For example, the Kuala Langat and Pahang Orang Asli communities she worked with told her that some of the medicinal plants they used to depend on were getting rarer and rarer.

“The Orang Asli have really strong physical and spiritual ties with the forests, even to the point they bury their ancestors in the forests, hence why they call these ‘ancestral lands’, hence the issue of indigenous land rights is tied to this disappearing knowledge too,” Syarifah Nadhirah ruefully noted.

Source: CNA/vt