912 Batu Road, the Malaysian story that took 15 years to be born! September 30, 2021 – Posted in: In The News, Reviews – Tags: Chowrasta Market, Japanese Occupation, Malaya, Papan, Singha the Lion of Malaya, Sri Bahari Road, Sybil Medan Karthigasu

Intan Maizura Ahmad Kamal

September 26, 2021

“WAS the book any good, Intan?” The question, fired ever so nervously by the elegant, bobbed-hair lady grimacing at me from my laptop screen, takes me by surprise. What kind of question is that? I mused silently before lobbing an excited smile in her direction.

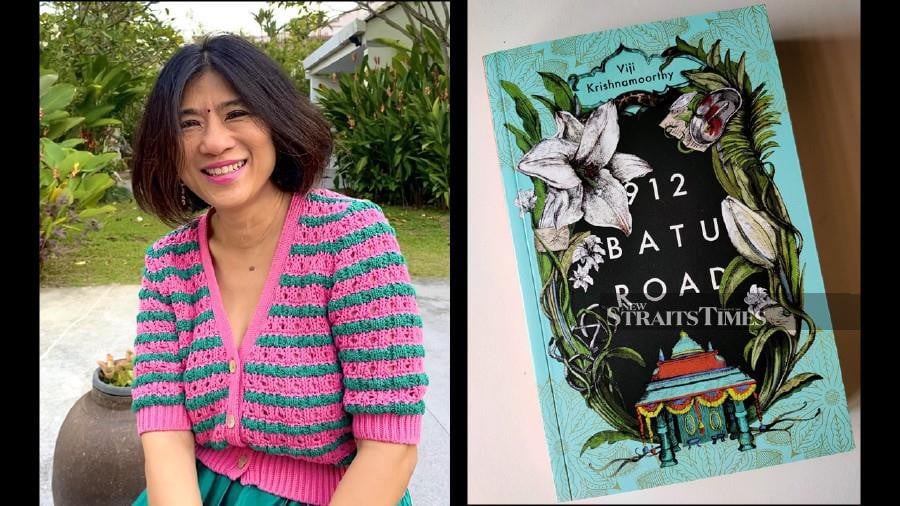

I mean, this is Viji Krishnamoorthy. She of The Lockdown Chronicles fame (an anthology of 19 Malaysian short stories that percolated from the Covid-19 lockdown published early this year), whose writing in the book left me feeling so inspired that I was compelled to tell anyone who’d listen that “… when I grow up, I want to write like Viji Krishnamoorthy!”

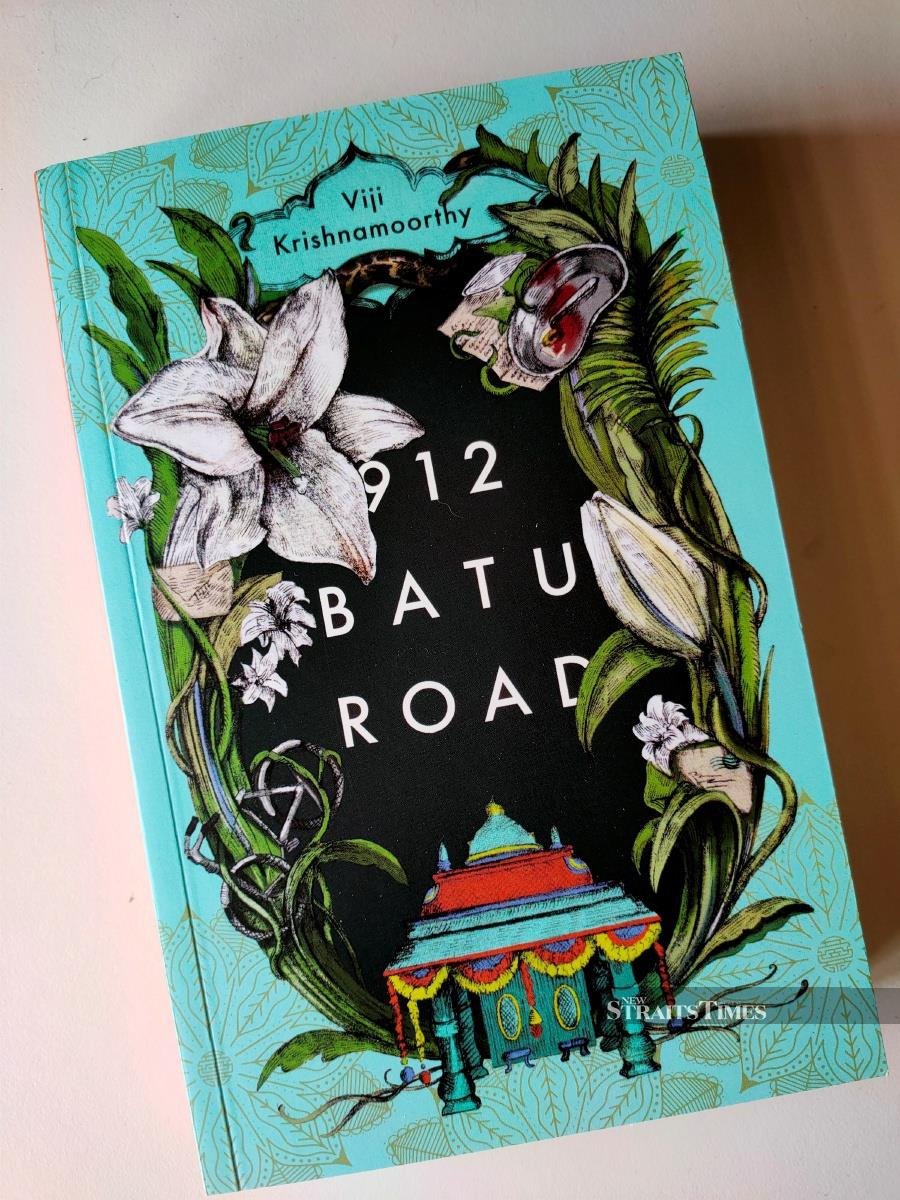

“Oh, don’t!” she shyly retorts when I tell her that. It seems compliments don’t really sit very comfortably with this 56-year-old author either. Her eyes light up when she notes a flash of teal green making an appearance in my hand.

“I managed to finish this, Viji,” I exclaim, triumphantly pointing to her book, 912 Batu Road, a sweeping debut novel, which deftly weaves together nostalgic history, vibrant fiction, and fascinating family. “At least I didn’t take as long as you did to finish writing it!” I can’t help but to add mischievously.

And we both break into knowing laughter.

As the story goes, the book, which centres on the life of a closely-knit South Indian Brahmin family living at 912 Batu Road, has had several births — breached, delayed and overdue.

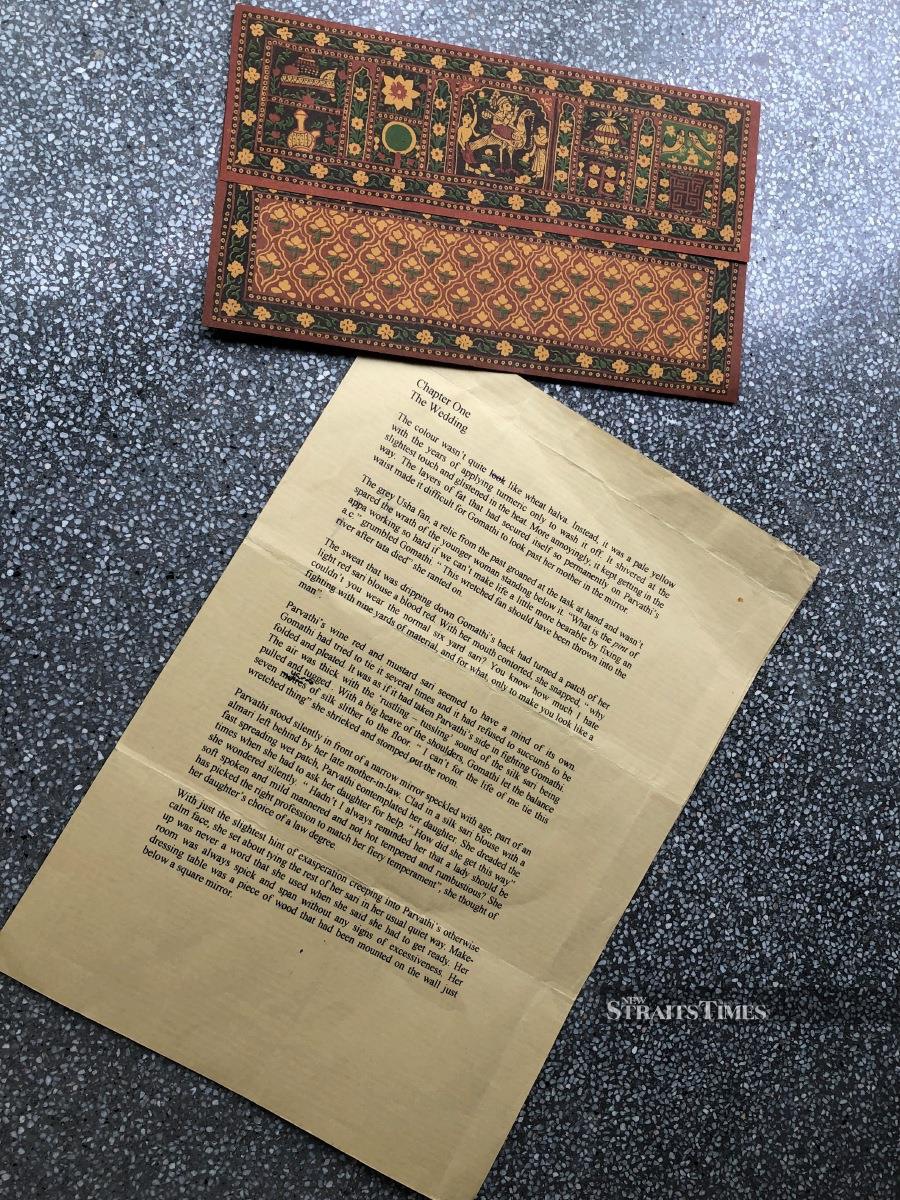

It originated as a chapter handwritten on an auspicious turmeric-coloured letter paper, a birthday gift to her husband, Ranjit. It’s taken 15 years or so for this teal green gem in my hand to come into the world.

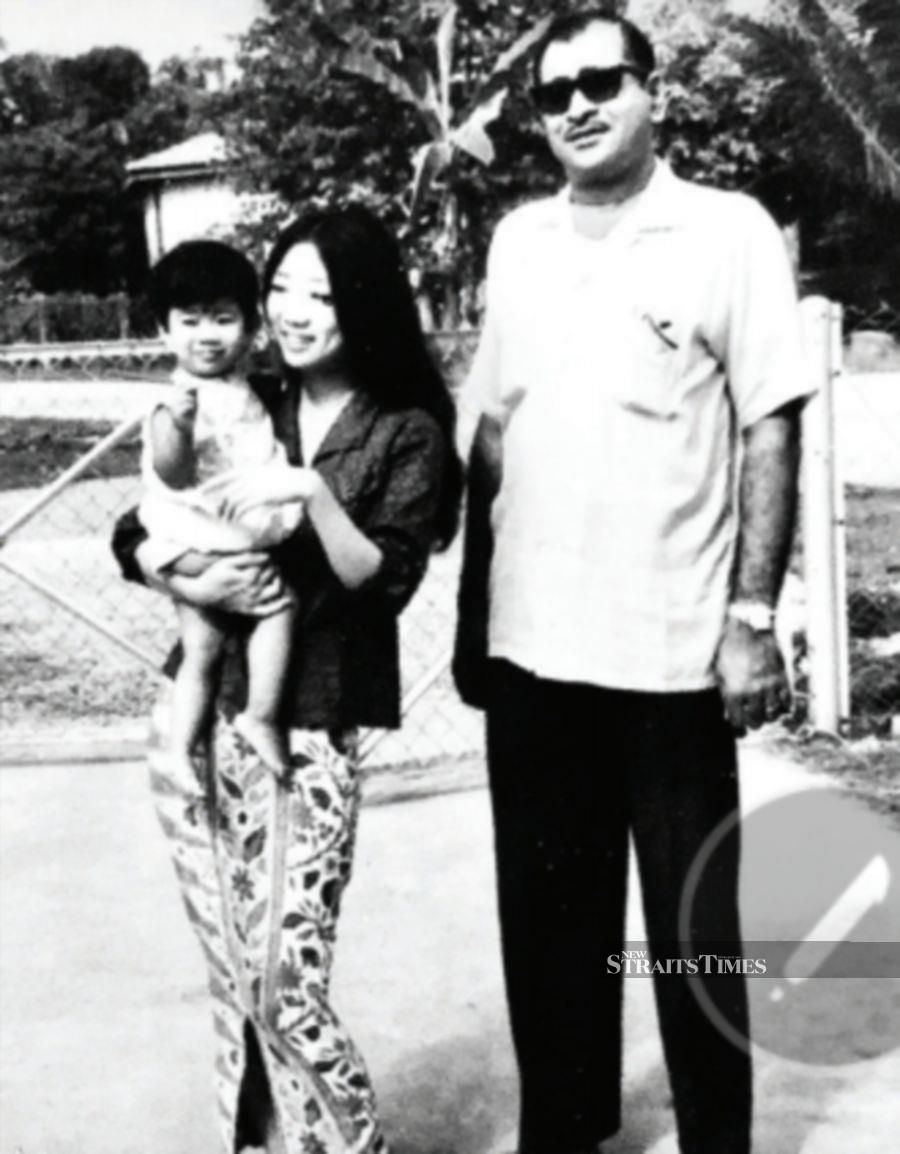

“I actually completed the book years ago,” confesses Viji, who was born in Ipoh, Perak, to a Tamil father and Hokkien mother. Adding sheepishly, she says: “I became quite a reluctant writer, to be honest. It took me a long while to gather the courage to do something with it. When it went to my publisher Roz Chua, she saw promise and I saw doubt. A lot of self-doubt.”

“But why? You’re such a great writer,” I can’t help blurting out, incredulity lacing my tone. Her exaggerated eye roll is her silent answer to my outburst.

Shrugging her slight shoulders, the mother of two muses: “I think you always worry about putting yourself out there. When you do something like this, which comes from somewhere quite deep within, it’s like baring your soul and putting it out there for everyone to prod and jiggle and nudge. It’s something I’m not comfortable with.”

Expression thoughtful, Viji, who previously worked as a freelance writer for several magazines, adds: “I worry about how it might be perceived. People might think that just because she can string words together, doesn’t necessarily make her a good writer. To be honest, I also feel very uncomfortable with the word ‘writer’.”

FROM THE BEGINNING

“If I were to really take it right back, to use a very crude word, the ‘preconception’ phase, it was actually from letter-writing,” replies Viji when asked about the initial seed for the book.

It seems that Viji and Ranjit, her then-boyfriend-now-husband whom she met in London as students, used to be avid letter writers. Those precious missives, she proudly confides, are currently stored in two tins at home.

“Back in the 80s, we had no access to phones like we do now,” elaborates Viji, who studied economics, adding: “So, we used to invest a lot of our pocket money on aerogrammes that we’d send to each other, especially if I returned home for the summer, and Ranjit stayed behind at his uncle’s house in England.”

Their letters were filled with news of their daily grind; the things they did and saw. “I was an avid observer,” declares the author, adding: “For example, when I was in London, I used to travel on the tube a lot, which gave me ample opportunity to people-watch.”

She’d often wonder what kind of lives they led and who they were. And all these observations she’d jot down in her notebook, some of which she would share in her letters to Ranjit. In turn, her boyfriend would often tell her how funny she was in the way she wrote.

Eyes dancing at the recollection, Viji shares: “He used to say, ‘You have a way of describing something that makes it come alive for me. Maybe you should consider writing a book!’ Of course, that thought never crossed my mind.”

Fast forward to when the couple completed their studies and were finally married. Viji recalls it so happened that Ranjit’s birthday was coming up, and she was contemplating what to give him for a present. “I really had no idea, so I thought why not I write him a chapter as a letter. It was a pretty lame present, really! But I did it anyway!”

They were in Pangkor on holiday when she presented him with that chapter, written on a very pretty Indian letter-writing paper. “I remember he said, ‘Oh, we really have to do something about this.’ I said, ‘no’, and just left the thought there,” recalls Viji, with a smile.

But her husband was persistent. He kept urging her to reconsider, chiseling away at her resistance, day by day. “I eventually agreed,” says Viji, tone sheepish.

She shares: “The first thing I told him I needed to do was to give it a past. And that past would have to be a story of a Tamil Brahmin man who migrated to Malaya in the 20s, which would have been the kind of journey my grandfather might have made back then.”

She admits that having never met her grandfather (he died before her father was even married), of course she can’t possibly know what his journey was like. But she was determined to include it anyway.

“That sort of festered as a juxtaposition to the story in the present,” continues Viji, adding: “Then, to draw the letters in, I thought it would’ve been quite nice to have the letters that Rangaswamy, (grandfather to Geeta, the protagonist in the story) wrote to his father in the village in India as a kind of a nod to the letters that I used to write as well.”

Discussions between husband and wife ensued thereafter, and Viji finally knuckled down to the task, writing furiously at her dining table while her young children were at school. But it proved to be quite a lumbered process. The writing would start, and then stop, and then start again. And so it went on — in this vein. “Like I said, I was quite reluctant to write,” she exclaims, chuckling softly.

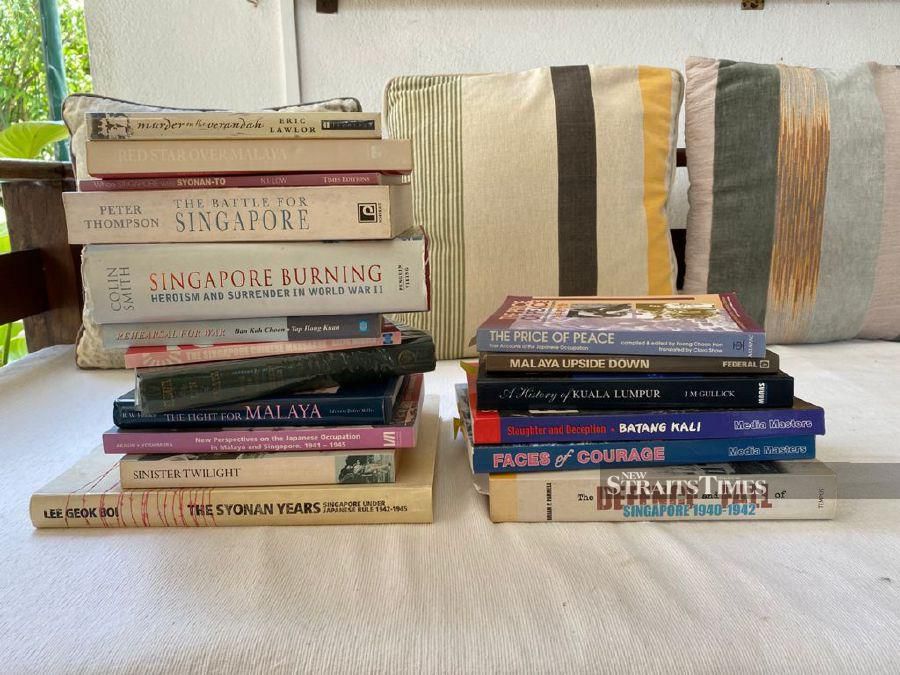

Her husband, she remembers, threw himself into the “project” in earnest. He’s credited for doing much of the research, although Viji did a lot of reading too. “We ploughed through and read the books together. And we’d talk about it, discuss it, and then try to imagine.”

Brows furrowing as she attempts to recall those early days, Viji tells me that it was all about using her imagination every time she looked at visuals and read all the books. “I had to try and immerse myself in that head space and imagine what it would have been like — the sounds, smells, colours and so on.”

Suffice it to say, it wasn’t an easy exercise. “That’s where the empathy comes in,” continues Viji, adding solemnly: “It’s the empathy that allows you to take yourself out of point A, and then put yourself into the shoes of someone else. You try and walk in it without passing judgment and asking too many questions. You just feel. I was feeling my way around it, albeit in the dark a lot of the time.”

Leaning closer to the screen, she confides that there were so many gaps in between when she was writing the book. “I’d write a bit and then take years off before returning to it. I think by the time I finally sat down to finish it, it was already 2010,” recalls Viji, who spent her early school years in Kuala Lumpur and later, at a boarding school in India.

BIRTH OF THE BOOK

Years passed and Viji’s completed story remained silently in the pages, hidden in the shadows of her home. It was only in 2018 that she decided to do something about it.

“I had friends who’d read it. And of course, my husband was pushing me. My friends told me not to be silly and that I’d come so far with it to just leave it hiding in the dark. And that’s how 912 Batu Road finally found its way into the light!”

Smiling shyly, Viji, who despite being half Indian and half Chinese, was brought up in a very Tamil household, shares: “Remember that gift I gave to my husband for his birthday? Well, the first chapter of 912 Batu Road is that very letter, albeit with some tweaks and amendments.”

Asked why she decided to centre the story on a Tamil Brahmin family, Viji, who’s well versed in Indian classical dance, explains: “I just felt that while so much have been written about Indians moving to America and the West, there’s hardly been anything about them coming to Southeast Asia or this part of the world. I thought that would make for an interesting angle. Incidentally, the Tamil Brahmin community is very small. There are 300 families only in the country.”

For those curious whether any of the interesting characters in the book has been drawn from anyone she knows, Viji is quick to reply: “Definitely not. Everything’s been drawn from my observations of people — in the community and outside of it.”

Despite her initial reluctance to embark on this book journey, the self-confessed dreamer shares that she enjoyed writing about the past.

“That was interesting. For example, there was a pull writing Elaine’s story (a character from the past who painfully lost her beloved son) because as a mother, writing about grief and of losing one’s child… it wounds you on such a deep level. I found that very hard and even now, when I read that part, it still touches me deeply.”

With so many characters in the book, does she have a favourite? Viji beams before answering: “I love Tochi! He’s a dresser at a government hospital in Penang. I loved writing about Tochi because there’s something so innocent about him.”

Adding, she says: “He was so gullible and so willing. He always looked at everything half-full and kept believing. There was so much good in him, I felt. I really enjoyed his escapades with Gurchan (Gurchan Singh, also known as Singha of Malaya, the policeman who went undercover and kept the Malayan people abreast of the true events that were unfolding during World War 2).”

FITTING TITLE

Flipping the book in my hand, my gaze lingering on its exquisite cover illustration by Anusha Jean Ramesh, I point to the title. “912 Batu Road is someone’s address?” I ask. Again, she smiles before replying: “When I bought my first car, a Proton Satria, I told the runner I wanted to have either the numbers 219 or 321 as my number plate. The latter because it was my room number, and 219 was Ranjit’s number in our hostel. He returned and told me he couldn’t get either. But he could get me 912. I took it.”

Continuing, Viji shares that she later drove the car to her aunt’s house. “I remember as she was walking out, she was holding a prayer tray in her hands. The moment she saw my car, she stopped in her tracks.”

Adding, Viji says that her aunt proceeded to ask her in Tamil what she knew about the number 912. “I said, ‘nothing’. She then told me that 912 Batu Road was the house that my father was born in. That was a piece of history I had no idea about,” remembers the author.

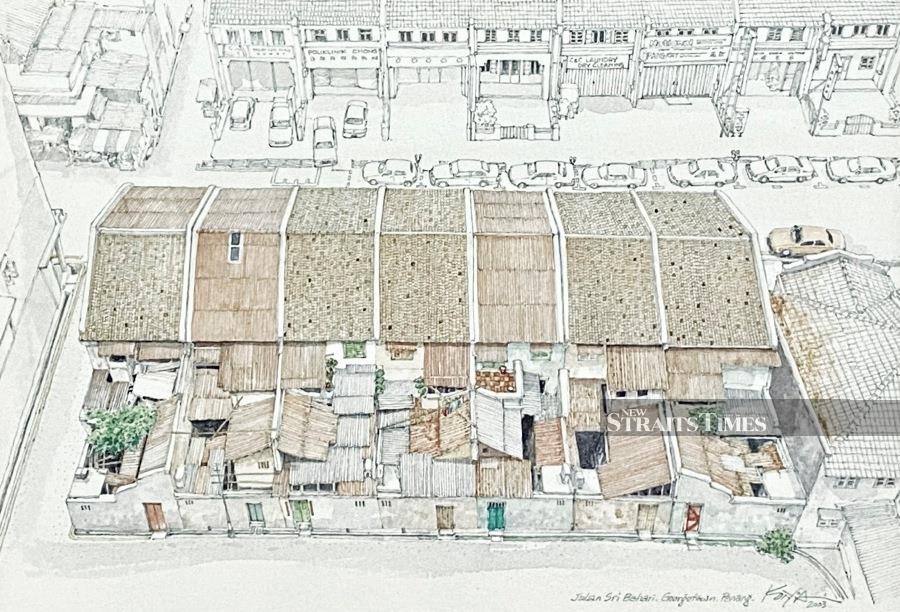

So, Viji thought it only fitting to name her book 912 Batu Road because so much of the past is set in a Tamil Brahmin house.

Continuing, she shares: “According to my aunt, Batu Road is where the MARA building stands today. It was a house given to my grandfather by the British during his service as an assistant labour commissioner for the British government then.”

Any plans to do a part 2? I ask the author, throwing her a mischievous look, already half knowing what her response would be.

“Nooooo,” she wails in return. “Aiyoooo, please lah, Intan! Actually, no one’s asked me to do that yet. But if you ask me whether there are any characters in the book that could be further developed, I’d say it’s Tochi and Gurchan. It’d be cute to see where they might go. But no, I have no such plans. And I’m NOT going to give my husband another letter as a present!”

LOVE OF BOOKS

Growing up, Viji’s favourite subjects at school were English and English Literature, and she’d always had a love for the written word ever since forever. Smiling, she confides: “I was always aware that every time I started a book, a new adventure would be waiting for me. Books were a large part of getting my mind to travel. Because back then, we never went on big, fancy holidays. We only went to Morib and Port Dickson!”

Books, continues Viji enthusiastically, completely opened her mind. “To things like lacrosse and midnight feasts. I lose myself in books. I can smell it, taste it, feel like, and touch it. It’s literally pulsating. And I think when you read avidly and across the board, that kind of takes you out of your own little world.”

To write well, it’s important to read, believes Viji. “The more you read, the better you write,” she says, before advising: “Read outside of your comfort zone as well; not just things you like. If you don’t like it, stop. I’ve come to a stage in my life where if I start a book and by page 10/11/or 12 it still doesn’t grab me, I’ll stop. Life is too short to torture yourself!”

Reading different perspectives also helps, she adds. “For example, perspectives that are unfamiliar to you. Doing so makes you question. I think you need to be curious. And when you’re curious about life and how other people live, that informs the kind of writing you ought to do, I think.”

Viji admits to having many favourite writers. “I love John Steinbeck! I always say his books must come with me on my final journey. I also love A.A. Gil, the British journalist, critic, and author. I happen to think that he’s the cleverest man on the planet. I like writers who can transport you to another place.”

She’s also a huge fan of the Italian novelist Elena Ferrante. Eyes shining, Viji, who continues to keep a diary to this day to jot down her observations, gushes: “When you read her book, you tend to read it in an Italian accent — in my case, it’s a crap Italian accent — and at a slightly faster pace because she makes it three dimensional, in the sense that her words dance for me. If only I could do that!”

Turkish novelist Elif Shafak gets her excited too. “The first book of hers I read was 40 Rules of Love. She REALLY took me on a journey that I’d never been on before,” shares Viji, elaborating: “A lot of her writing is steeped in Istanbul. I’ve been to Istanbul twice and I loved it. I can understand why she loves Istanbul so much. Her writing transports me there and it’s like going on a magic carpet ride with her.”

Awe lacing her voice, Viji, a self-confessed interior design junkie with a love for mid-century modern furniture, muses: “I always wonder where their next idea comes from. I mean, how are these writers able to keep churning books out? It’s wonderful to have such prolific imagination. I mean, with 912 Batu Road, you’re writing against a historical backdrop, so you have something there to hold you up. But to write something completely non-historical? It’s not easy.”

JUST VIJI

Does she ever get writer’s block? I ask, thinking of the endless hours I sometimes spend looking at my peeling walls in the semi-darkness just waiting for that first line to hit on my own articles.

“Definitely,” she replies, head bobbing in response. So, what does she do? “I just walk away and do jigsaw puzzles. Back then, it was my greatest escape. Now, if I’m writing an article or something, then mahjong is my escape. I also read sometimes even though some people say if you’re in the middle of writing, it’s not a good idea to do that. For me, it’s a wonderful escapism.”

Viji Krishnamoorthy is refreshingly unassuming. As I’m writing this, I’ve already seen her smiling face peering out from several publications. Her debut novel has certainly courted a lot of attention. “You’re already famous lah, Viji,” I tease, before chuckling at her horrified reaction.

Tell me something else I might not know about you that could be quite interesting, I probe, as I slowly begin to gather my things together for my next Zoom interview.

The soft-spoken Pisces beams and replies: “I’m a 60s soul! If I could travel back in time, I want to go back there. I love the fashion, the music, the whole sense of couldn’t care less. It was so liberating. You could really be who you want to be. I like the idea of getting lost in that!”

First published in NST on 26 September, 2021