Mak Yong: A rich artistic heritage August 13, 2019 – Posted in: In The News

By Alan Teh Leam Seng – April 7, 2019 @ 8:20am

UNITED Nations (UN) special rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, Karima Bennoune’s call for the Kelantan state government to lift the ban on the Mak Yong performance and other traditional Malay art forms caught the attention of many Malaysians, including myself.

Her comments made on the side-lines of the recently held 8th World Summit on Arts and Culture Kuala Lumpur 2019 made sense. Instead of stifling the growth of some of the oldest performing arts in the world, we should actually be celebrating and appreciating them as part of our rich culture and traditions.

My interest in Mak Yong grew after learning that it was accorded recognition back in 2005 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco).

The move was made at that time to prevent the ancient art form that has existed in this region for nearly a millennia from fading away as a result of strict restrictions imposed by the Entertainment and Places of Entertainment Control Enactment passed by the Kelantan state assembly in 1998.

The effects of the legislation were far reaching. It greatly reduced whatever little interest that was left for Mak Yong performances which once saw widespread following among local Kelantanese in the 19th century.

Today, the countless troupes that once toured the countryside and received near pop-star like reception everywhere they went have all but disappeared. In their place are state-sanctioned artistic ensembles that dish out severely watered-down versions which are considered more puritan.

Curious to know what Mak Yong performances were like in their original form, I rummage through my collection of references in the hope of uncovering some interesting titbits. Fortunately, Lady Luck is on my side. Within the hour, a small pile of related works by several renowned Malayan historians and academics, especially those by Tan Sri Datuk Dr. Haji Abdul Mubin Sheppard, lay waiting to whet my inquisitive appetite.

LOCAL MALAY CREATION

Soon, an astounding tale of an art form solely devised by our ingenious Peninsula Malays without an exact parallel or prototype elsewhere in the region begins to unfold. Always performed by a cast of young and attractive women who played all the parts save for those of comedians, this Malay dance drama seamlessly combined epic romantic themes with interesting dance movements, operatic singing and broad comedy.

Even though the actual origin of the name Mak Yong has been lost to the annals of time but, according to Sheppard, this ancient art form could have started off as a form of ceremonial propitiation of the spirits and the name, a corruption of Mak Hiang, the Mother Spirit whom Peninsula Malays in the past trusted to watch over their rice crops and keep them safe.

Historians believe that Mak Yong came into existence at the court of the Malay ruler of Pattani (now South Thailand) at least 400 years ago and spread southwards to Kelantan some two centuries later. In one of the earliest accounts, 17th century European explorer, Peter Flores wrote briefly about a Mak Yong performance he witnessed during a banquet given by the Queen of Pattani in honour of a visiting Pahang Sultan in 1612. Since then until the second decade of the last century, multi-talented palace troupes entertained rajas, local chieftains and their guests.

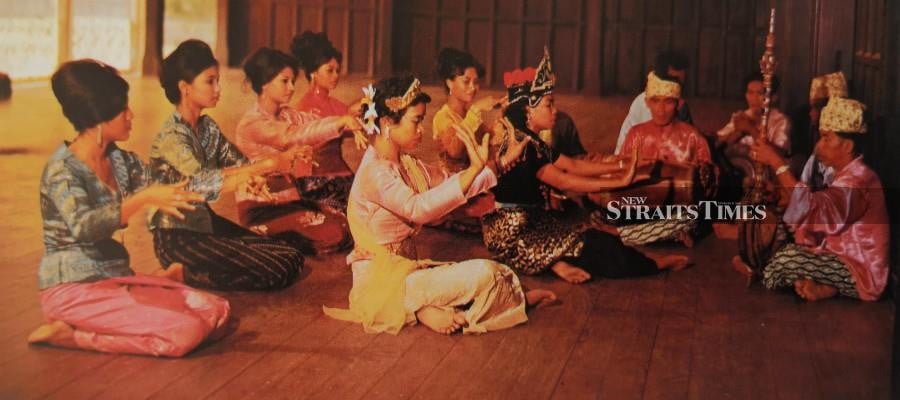

By the 19th century, Mak Yong had become the dominant form of Malay upper-class entertainment. Usually held in an audience hall with three walls and an open side, the performance would begin at nine o’clock at night with the arrival of the performers and members of the orchestra who would sit in the centre of the polished wooden floor and await the arrival of the Raja and his guests who’d occupy cushions along the three walled sides of the rectangle.

Meanwhile, members of the royal household were allowed to watch from the open side of the hall. Once started, the performance would continue without any breaks until the raja indicated his desire to retire for the night.

FLEXIBLE APPROACH

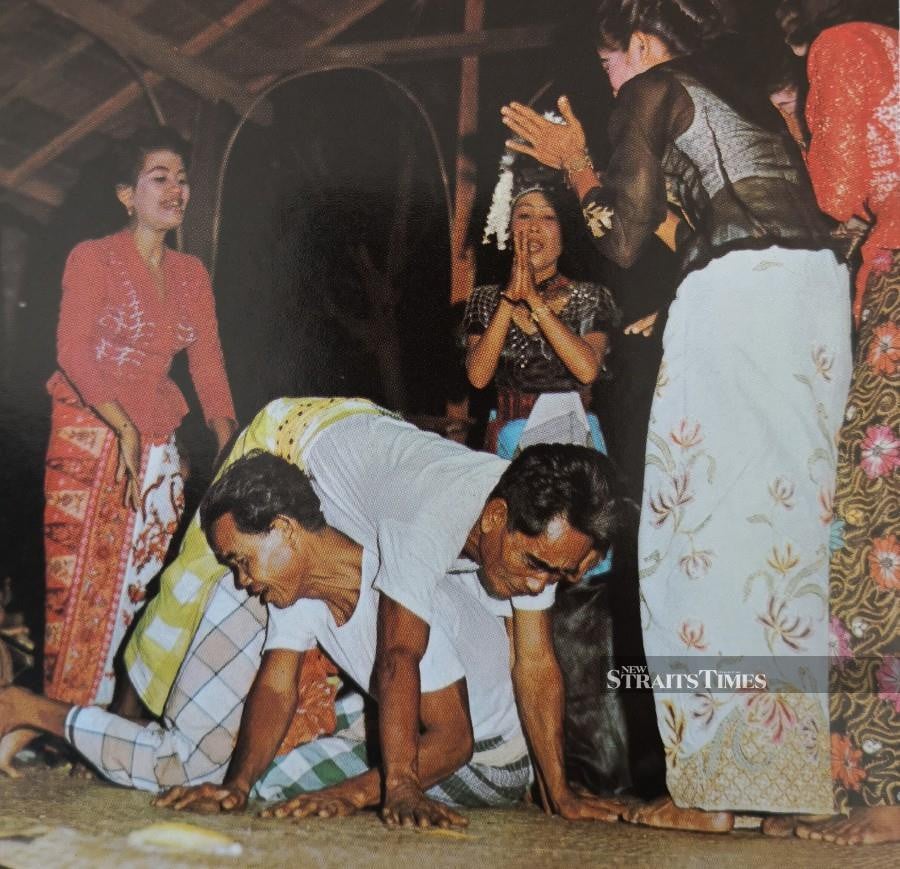

The pace of the Mak Yong performance is unhurried and the story could continue for as long as four to seven consecutive nights. With no written text and the dialogue varying from one performance to another, leading actresses had ample opportunities to display their talents as solo singers and dancers. The comedians, the only males in the cast, usually took on secondary roles as palace servants.

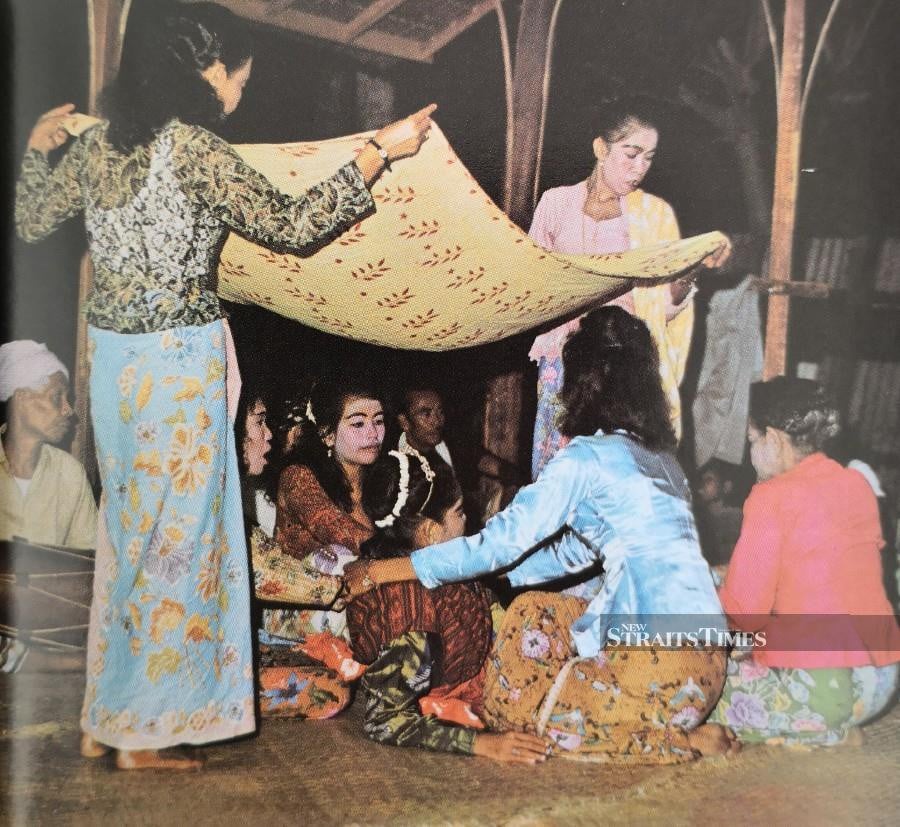

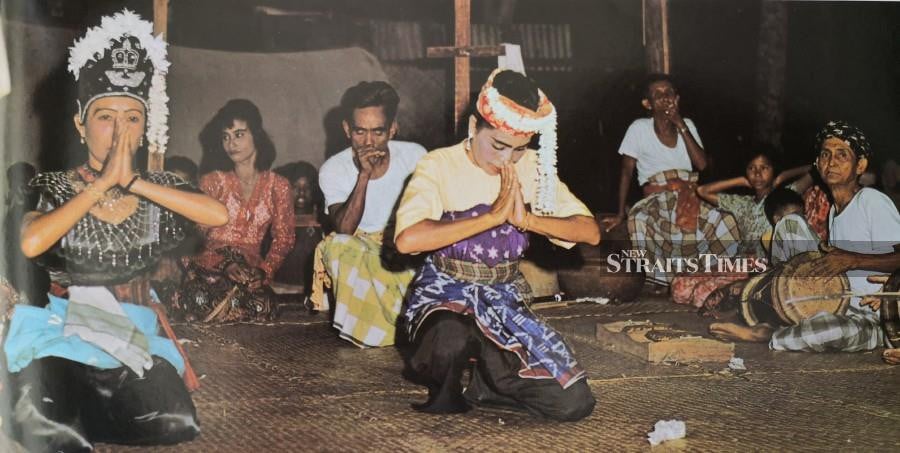

Mak Yong performances always open with a 20 minute solo, sung by the leading actress and supported by the voices of the cast. It would be followed by the introduction of each individual cast member. An hour may pass before the female actress who plays the part of the male hero makes her grand entry.

The choice of songs played during a Mak Yong performance would usually be decided by the rebab (spike fiddle) player in consultation with the leading actress before the start of the performance. His performance is key as the rebab melody not only leads the orchestra but also the singers and dancers throughout the performance.

Only the tunes remain constant while the performers are given freedom to improvise the lyrics to suit each occasion. The melodies are usually associated with romance, sorrow, travelling and revelations of secrets. To date, there are 35 Mak Yong tunes on record but historians believe that there must have been many more in the past.

Apart from the rebab, four other instruments form the Mak Yong orchestra – two gendang (double-headed barrel-drum) and a pair of tawak-tawak (deep-rimmed hanging gong). Prior to each performance, a little water would be poured into the bottom of the tawak-tawak to improve the tone and prevent the gongs from cracking.

SUPERSTITIONS ABOUND

Relics of a web of superstition which once surrounded the gongs require their innards to be filled with raw cotton threads, small pennants and flowers. Apart from that, performers would apply water on their throats prior to the performance and do the same again later in the evening to ensure that they maintain a clear and sweet voice.

Performers rely heavily on their performing skills as stage props are scarce. The magic wand, made from seven strips of bamboo, stands out prominently among the few simple ones that the performers have at their disposal. It would be carried by the raja or prince in the story and used to beat the comedians when they get out of hand.

When the story calls for a magic kite, one of the comedians would remove his long batik head-cloth and deftly fold it over the wand. In the story where the queen gives birth to a triton shell, it’s represented by a bundle of head-cloth.

A rogue elephant, which appears in the story The Arrow of Fortune, takes the form of a head-cloth twisted to resemble an elephant’s trunk and promptly hung below a comedian’s nose. In those days, members of the audience were accustomed to exercising fertile imaginations and they wouldn’t have expected anything more.

As if to counterbalance the lack of stage props, the costumes worn by the performers are elaborate and costly. The leading parts in all Mak Yong plays each have their own special names and set costumes, regardless of the story being played. The leading actress plays the raja role called Pak Yong. Another who becomes the young heroic prince is known as Pak Yong Muda. The part of the raja’s consort is referred to as Mak Yong while that of the princess is known as Puteri Mak Yong. The comedians are called Peran and their senior is named Peran Tua.

The Pak Yong and Pak Yong Muda share near-similar costumes which consist primarily of a stiff velvet head-dress studded with small jewels and a row of sweet-scented white jasmine buds. Both wear close-fitting collarless and short-sleeved shirt made of yellow silk and trousers, made from the same material in either black or dark blue hue. The latter are covered by a knee-high dark red sarong fashioned from hand woven silk.

Both the Mak Yong and Puteri Mak Yong wear Malay-styled long-sleeved silk blouses fastened down the front with three gold and jewelled kerongsangs. Their silk sarongs reach from waist to ankle and are secured by a silver belt. All the cast members would be barefooted as the tales they act out are in the presence of the raja, in his audience hall.

CAPTIVATING TALES

Curious to know more about Mak Yong stories, I turn to another of Sheppard’s work which details no less than five of those that are most captivating. Among them, the popular ‘Triton Shell Prince’ tale perfectly captures the very essence of this enchanting performing art form.

The story begins with the raja (Pak Yong) awaiting the birth of his child. His wife (Mak Yong), who’s the daughter of the King of the Sea Dragons, gives birth to a large triton shell and the raja, making no allowances for her aquatic origin, drives her from the palace in a fit of anger. She seeks refuge with an elderly hermit (Peran) living by the forest edge.

A few days later, while collecting forest fruits, a little boy emerges from the triton shell and grows quickly to the size of a 15-year-old youth (Pak Yong Muda). He joins a group of palace children in causing mischief and that prompts the raja to instruct his gaoler (Peran Tua) to arrest the newcomer.

Arriving at the palace, the raja orders the execution of the youth when he raises a ruckus and behaves disrespectfully. The raja’s sword and royal elephant, however, prove ineffective. When ejected out to sea with a large cannon, the prince is rescued by his maternal grandfather who sends him back to land.

With the help of magical powers, including an invisible ape-skin cloak obtained from an ogre, the prince surmounts all obstacles and is finally proclaimed heir apparent. Despite its many fictional and seemingly far-fetched tales, Sheppard’s definitive work also reveals a dark and tragic Mak Yong secret that is both part of Kelantan history as well as responsible for dealing a lethal blow to the art leading to its unfortunate decline.

ILL-FATED LOVERS

This historical event, which took place in October 1912, revolved around a young Mak Yong actress in the sultan’s palace named Urau. At the tender age of 16, her beauty, coupled with the sweetness of her voice and captivating performing skills, made her the automatic choice for Pak Yong Muda, the young prince.

Urau, like scores of others, had been hand-picked by keen-eyed courtiers when she was just nine. She was inducted into the palace penetralia and trained daily without fail. Three years later, Urau’s first appearance saw her taking on the role of a maid-in-waiting.

Among those who sat, night after night, at an obscure end of the audience hall was Tuan Yit, a handsome 18-year-old youth who served as a royal valet. He was aware that Urau was the sultan’s favourite actress but infatuation got the better of him.

On that fateful night, he waited for Urau to retire to her room in the palace grounds before asking for and gaining admittance. Palace spies speedily reported the incident to the sultan who immediately despatched two guards to breakdown Urau’s door and stab Tuan Yit with a keris while he lay beside his lover.

Urau sprang to her feet, straddled the dying youth and wailed several times, stating her wish to die as well. The guards obliged and she fell without uttering a word. It was said that torrential rain began to fall as soon as her head hit the floor and by the time the bodies were taken out at dawn, it was difficult to even find five feet of dry ground for their burial.

Over the next 12 days, Kota Bahru experienced the worst flood of the 20th century. It appeared as though the heavens were weeping for the ill-fated lovers as the annual inundation wasn’t due for another month.

The devastating flood destroyed rice crops for kilometres on end. It was named Bah Urau (Urau’s Flood) as the water rose with strange rapidity on the night of her death. After the waters subsided, it was said that the sultan completely lost heart in Mak Yong performances.

That rang the death knell for Mak Yong as no traditional art form of such high quality could prosper without royal patronage. By the end of the first quarter of the 20th century, palace and other princely establishment troupes were forced to offer their services to the general public. But with an irreducible minimum of 16 performers, including musicians, travelling Mak Yong troupes soon found themselves on the wrong end of time.

In 1968, eminent American musicologist Professor William Malm visited Kelantan and discovered that no authentic Mak Yong actress or comedian had given a performance in the traditional palace style for more than three decades! Revival efforts by the Malaysian Society for Asian Studies a year later helped but the momentum couldn’t be sustained.

At the end of my research, I can’t help but feel a tinge of sadness for the fate of Mak Yong performances in our country. If only the recent call to reverse the ban and rejuvenate this ancient home-grown artistic art form can result in success, then perhaps it will be proof that the magic of the Mak Yong is indeed truly immortal.

This article first appeared in The New Straits Times on 7 April 2019