She who wants to see Penang at its classic best October 15, 2018 – Posted in: In The News – Tags: history, Khaw Sim Bee, khoo salma, Penang, Pulau Pinang, Pulau Pinang Magazine

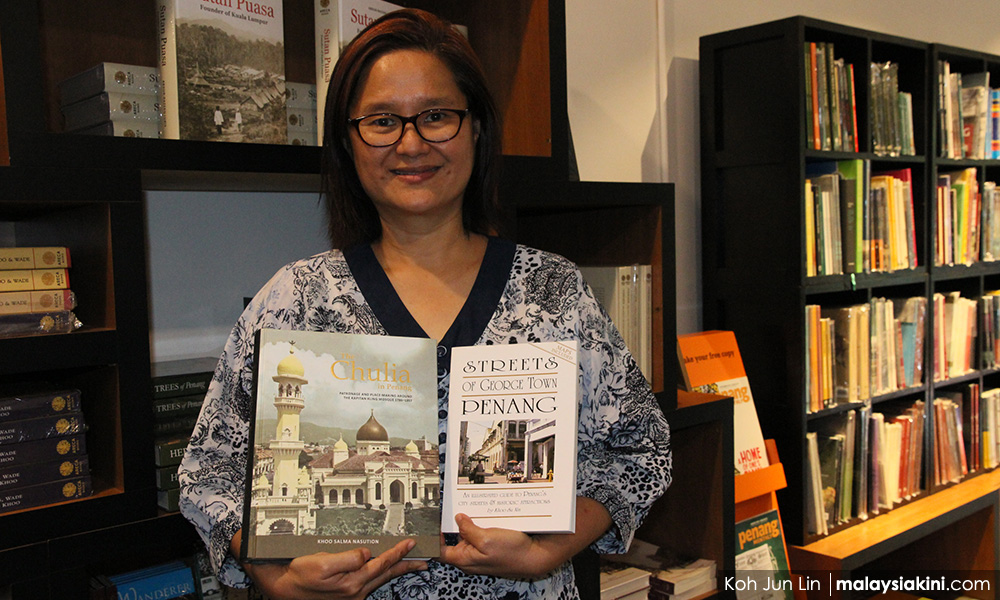

George Town native Khoo Salma Nasution @ Khoo Su Nin, 55, wears many hats in championing the Penang capital’s colonial era heritage.

She was the president of Penang Heritage Trust, and prior to that was involved in the group’s successful lobbying to the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) to list George Town as a World Cultural Heritage Site in 2008.

Khoo Salma has written multiple books about Penang’s history, some of which were published through the publishing house Areca Books that she co-founded with her husband Abdur-Razzaq Lubis in 2004.

One of her books, The Chulia in Penang that talks about the Indian Muslim community on the island, had gone on to win the International Conference of Asia Scholars (ICAS) book prize in 2015.

She is also a custodian of the Sun Yat Sen Museum in Penang, which was once the house of her grandfather, Ch’ng Teong Swee.

In campaigning to preserve Penang’s heritage, Khoo Salma lobbied against overdevelopment, swiftlet nest farming, gentrification and the Penang Pan-Island Link highway project.

She had even served a one-and-half-year stint as Penang city councillor, beginning in 2017 as the representative of the NGO, Penang Forum, in the Penang Island City Council.

But the road to becoming a heritage activist – or indeed what to do at all – wasn’t clear at first when Khoo Salma left Duke University with her liberal arts degree in 1985.

This is her story in her own words:

I was born in Penang – Khaw Sim Bee Road – in 1963, so I’m Penang Hokkien. I have one sister; an elder sister. The lingua franca (in Penang) was Hokkien and it’s very much you feel like this is your hometown; the streets have lots of trees; if you want to go to Seberang Prai you take a ferry; you can do shopping along Penang Road or Campbell Street, in those days there were no shopping malls. Once awhile, you take a beca (trishaw) because that’s the means of transport.

I went to St George’s Girls’ School, and then I took liberal arts at Duke University – kind of mixture of philosophy, psychology and visual arts.

I always wanted to be a writer, but I have two kinds of… One is visual. I’m a very visual person, but also, I wanted to be a writer. So, there were two things that I wanted to pursue. But in the end, I’m doing more writing but still I’m involved in books, in the design of books, and mapping.

I didn’t mix that much with Malaysians (while in the US), but there was one meeting with Malaysians in Boston where everybody said, “Oh, we must go back to Malaysia and do something.” That’s what I did, but then I found that a lot of people, from that generation, didn’t come back to Malaysia.

So, in the 1980s, many of us took something called Development Studies. Malaysia is depicted as the Third World. So how do you develop the Third World? You try to think about what it is that the country needs. Of course, people who are scientists will contribute in that sense.

But when I came back I knew I wanted to do something for Malaysia, but I wasn’t sure what it was. After a few years I found that, you know, what I wanted to do was to get people to appreciate Malaysian heritage, and especially built heritage. So, my strength is in understanding heritage conservation.

I felt that something that you know… It’s like you really feel that there is a need to do something or a need for something to be recognised, but people don’t recognise it. So, when I came back I wasn’t aware of this and took for granted my surroundings. But after I had travelled a bit came back, I said that, “Actually, Penang has a very nice built environment”.

In the late 1980s, people didn’t really appreciate it. Penang is a port, but by that time we had lost our port status around 1970. I understood that Penang was an important port and that’s why the buildings that were built were quite well-endowed; I mean they were very well built. They were built for people who were very affluent.

We are talking about… Let’s say the late-19th century up to the middle of the 20th century – up to the Second World War. So, you have this kind of Victorian or Edwardian-era buildings – which during the colonial era – the wealth came from the port trade.

But nobody knows. When you ask people, they don’t quite know what this trade was about, or who were the people who came through the port. The city was built because of the trade, but people didn’t quite understand it as a historical process. They were living in it, but they couldn’t describe it because everybody could only see a small part of it.

So, that piqued my curiosity.

I was actually a freelance writer and I was devoting a lot of time to the Penang Heritage Trust, which I joined in 1989. At that time, I was 26 years old. I was the honorary secretary. I was doing a lot volunteer work for the Penang Heritage Trust and was very interested in conservation.

Although I’m not an architect, I took all these courses on heritage conservation. At that time, not many architects were interested in heritage conservation, but I was very interested. And so I felt that I was spearheading interest in this field.

We organised talks and invited people to speak and introduce this whole idea that all these old buildings are not going to be one day replaced by new buildings. You must learn how to take care of them. That was my main role.

And then in the 1990s we tried to change the tourism paradigm by saying that tourists don’t just want to look at beaches. Actually, they would appreciate looking at the city because the city is different.

In 1998 we invited the Unesco regional advisor for culture to come and look at Penang and he said: “You should do something about it. You have not only cultural diversity, but you have – in some cases – cultures that have blended and fused and it’s something quite unique.” And so, then, we started this whole World Heritage nomination process, which ended with Unesco listing George Town as a World heritage Site in 2008. It took about 10 years to achieve this.

I was doing a lot of freelance writing. It’s kind of very frustrating to wait for opportunities, right? Actually, both my parents are teachers, so I had to learn how to do business the hard way. I’m kind of allergic to numbers… but both my husband and I are writers. My husband wrote this book Sutan Puasa: Founder of Kuala Lumpur. And then we moved on, and set up Areca Books.

We published our friends’ books and sometimes our books because what we write is very specialised and there’s no mainstream publisher who’s willing to publish something like that. Even if they were, they would say, “Oh why is it so specialised? Why don’t you write for a more general audience?” But this is what we don’t want to do.

We know that there are niche things that appeal to certain people. It’s kind of a knowledge that we want to share; certain knowledge that other people have also shared with us, so we ought to share it with other people. And to write narratives about our history, to help shape our understanding of Malaysian history.

I think my most successful book so far is something I wrote in 1993. It’s called Streets of George Town, which, in a way, started up the whole interest in what is now the World Heritage Site. That was 25 years ago.

It was basically telling the story of the streets. At that time, we didn’t have that much, and we didn’t know that much history. I mean it was a bit patchy, right? So, one way of putting it together was to go street-by-street. It’s a mixture of urban legends and some architecture. It’s quite a bit anecdotal.

Anyway, before that I was the editor of Pulau Pinang Magazine. That was a magazine about the culture and local way of life. So, it’s just to make Penang people conscious that they have something. At the time we didn’t think, “Oh it’s a unique product or whatever”, but you know, it’s something that is to be appreciated.

So then, after Streets of George Town, I wrote a few more books. But the one that won the prize is like a serious, a bit academic, book, which took a long time.

It took me like 17 years to write the book. But I did other things during that time. I didn’t just stop for 17 years but I started 17 years earlier and then I couldn’t finish it. So, I abandoned it, did something else, and it came back to it. So that one is called The Chulia in Penang, and that one won ICAS award.

Actually, my main passion is urban history. Basically, it’s understanding the built environment and the history of how the whole thing… How the city grew. So, you have to use maps, old pictures, and all that to reconstruct and also understand what were the economic drivers of that urban growth. I have a small group of friends that we’d just get together and then we just talk about these obscure things that nobody else seems to appreciate.

But what is great about George Town is that you could still read it. You know you can read the city like a book. You can look at something and you can try to understand what happened and then, when something was done. In Kuala Lumpur it’s very difficult because it’s been so overdeveloped with highways and all that. With Penang today, you can still get the feeling of… I mean even though things have changed, but the context has remained the same. You can still feel the context.

Moving forward? Oh, I have to work on another book on Penang, actually. I was starting to do that. Like a general book, not… I think Chulia one is too specialised for most people, but a general book on Penang is needed because now I know so much more than I did 25 years ago. And then when this environmental impact assessment report (on the Pan-Island Link) was released, I had to stop and just focus on fighting the highway.

So, I’m working on a general book on Penang, which I hope to bring out… I hope I can still finish it by early next year. — Koh Jun Lin

This article originally appeared in Malaysiakini, 15 Oct 2018.