French missionary’s WWII diary offers a glimpse of life during wartime in Penang August 16, 2021 – Posted in: In The News, Reviews – Tags: Clergy, French, Japanese Occupation, Missionary, Penang, Roman Catholic, WW2, WWII

Rouwen Lim

One can only imagine the significance of the moment when French historian Bernard Patary stumbled upon handwritten accounts dating back to the 1930s, in the archives of the College General in Penang, about 15 years ago.

This was a black hardcover notebook and numerous exercise books with brown covers. There were times when the author even wrote on loose sheets of paper that were then inserted into the book proper when it was safe to do so.

Entries were made almost daily – even if sometimes it was only one line – from March 1931 to September 1946.

But no one knew who this person was.

With a bit of deduction, sleuthing and piecing together of the puzzle, the answer started to emerge. This was not an easy feat as the writer took precautions and hid his identity, referring to himself in the third person in his writing, likely for reasons of safety.

“He was a prudent person, as he hid his ‘diary’. He was secretive as he never mentioned his name. Patary didn’t identify the author of the diary. I managed to put a name on the author because only three directors out of seven never left Penang island and finally, the author inadvertently betrayed himself with a lapsus calami (slip of the pen).

“On April 20, 1943, when the College General was making space for extra classrooms at the request of the Japanese authorities, he wrote: ‘The BVM [Blessed Virgin Mary] statue at the main entrance is parked in my office.’ The office referred to was the Superior’s office; from this we can conclude that the author was Marcel Rouhan,” says Serge Jardin, a French geographer and historian/author, who translated these documents.

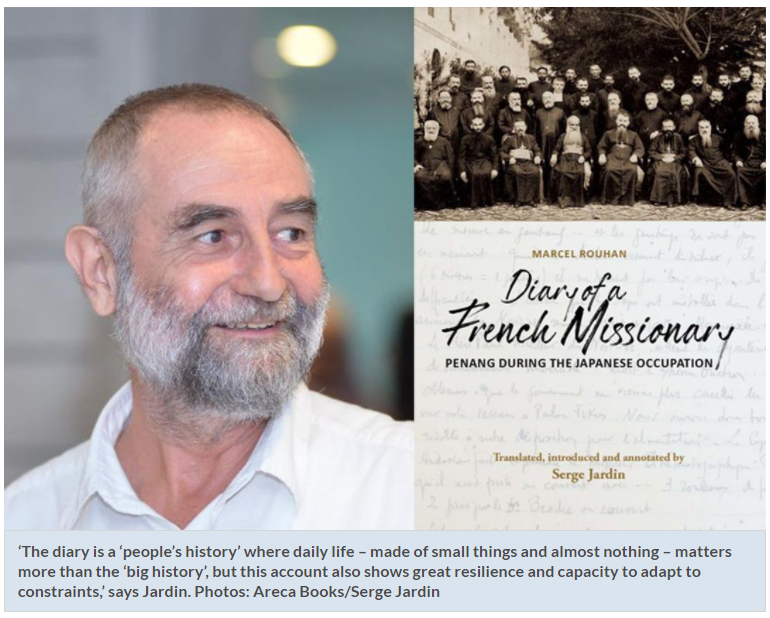

This English translation of the diary is published by Penang-based literary outfit Areca Books as Diary Of A French Missionary: Penang During The Japanese Occupation, with an introduction and annotation by Jardin, who has written books such as Rever Malacca, Malaisie: Un Certain Regard (with Sylvie Gradeler) and Malacca Style (with Tham Ze Hoe).

He is currently based in Melaka and runs a boutique bed-and-breakfast in a restored townhouse, together with his Malaysian wife.

Jardin discovered the existence of this Diary while reading Patary’s doctoral thesis on the College General. He then went to Penang to read the diary in the archives of the College, today’s seminary of the Catholic Church in Tanjung Bungah.

“For the historian, there is no greater pleasure than to be able to work on primary sources. After reading the diary, which comprised 286 manuscript pages written in French, I realised it was a pity that Malaysian readers will not have access to such a unique document of social history. So I decided to translate it into English and look for a publisher,” he says.

From a neutral’s view

Jardin notes that many books have been written on WWII, from all sides of the divide (British, Japanese and Malaysian), on military operations and on political aspects – sometimes to explain and most of the time to justify.

But this diary, he says, is a worthwhile venture for at least three reasons.

“Firstly, it is written by an outsider, a ‘Neutral’ as the French were called by the Japanese. The French Catholic priests were almost the only ‘white men’ to stay put until the end and share the struggle of the people during the Japanese occupation. Secondly, as it was not destined to be shared nor published, it possesses a great freshness and freedom of tone.

“And most importantly, it is about daily life, the war seen from the bottom, at street level. It is not about the freedom fighters nor the heroes, not about politicians nor soldiers, it is about the life of ordinary people. It is about adaptation, resilience and survival in time of war,” says Jardin.

Since its inception more than 350 years ago, College General has produced about 1,000 priests and trained more than 2,000 students. Its curriculum was no different from that of a major seminary in France. Latin was the language of communication until the 1960s.

“The College General was not a parish church opened to the public, and the Diary is an opportunity to enter a very closed and private world… life in a boarding school, made exclusively of male and religious students.

“You discover their programmes, their extracurricular activities, their leisure, their meals and so on. With a private document like the diary, you penetrate somebody else’s life and you start to see the past through their eyes. It is difficult not to have empathy, but you should stay alert. To understand is not to agree. You need to put things in perspective, to learn about the context,” he elaborates.

Apart from releasing this new book during the pandemic, Jardin is also currently working on A Fortuitous Encounter: Walks In The French Memory Of Malaysia and on the translation of The Account Of A VOC Mercenary In Melaka.

A practical man

Rouhan’s leadership and organisation skills came through in his writing, as did his determination to not endanger the lives and the institution he was in charge of.

“He could be very practical: ‘Better to have food in the store than to have notes in the safe’, surprising: ‘Father Denarie remains at the Assumption Church in the midst of the falling bombs and composes poems in his shelter while waiting’ or with a bit of foresight: ‘A wind of independence is sweeping through the empire’. Not to forget also that French red wine goes nicely with roast squirrel,” says Jardin.

Diary Of A French Missionary comes with a glossary, background on the College General, a timeline and other additional information to provide context for the reader. He adds that the book is accessible to all, noting that Rouhan’s writing style is clear and straightforward.

“The Diary is a ‘people’s history’ where daily life – made of small things and almost nothing – matters more than the ‘big history’, but this account also shows great resilience and capacity to adapt to constraints.

“It is a story of how the unimaginable becomes possible, and how, slowly, the possible becomes real, and finally, how survival becomes a way of life. Beyond the dichotomy where the traitors are punished and the heroes idolised, I hope this book can help show the (Japanese) occupation as more the 50 shades of grey, than the black and white period it was not.

“There is a thin line between freedom fighters and gangsters, between liberation and piracy. For instance, the actions and mindset of the people were not the same in 1943 and in 1945. After almost four years of war, the difference between Chinese, Eurasians, Indians and Malays paled in comparison with their common human conditions of exhaustion and hunger. As Rouhan wrote in July 1945, ‘Semua orang lapar’ (everyone is hungry),” concludes Jardin.

Reproduced from The Star, 15 Aug 2021